1. Introduction

The study of human cognitive abilities has flourished, albeit not without controversy (Richardson, 2002), since Spearman’s (1904) seminal finding that performance on cognitive measures, course grades, and even rating of “common sense” are positively correlated. Based on these findings, he concluded “that all branches of intellectual activity have in common one fundamental function (or group of functions)” (Spearman, 1904, p. 285). Ensuing debates centered on whether human cognition should be best understood as a unitary set of competencies known as g (general intelligence), as argued by Spearman, or a constellation of relatively unique abilities, as argued by Thomson (1916), Thurstone and Thurstone (1941), and others. It is now accepted that human cognition is hierarchically organized with narrow specific abilities (e.g., arithmetic, geometry) at the lowest level, broad domain-specific abilities (e.g., mathematical) at the next level, and general ability at the highest level (Carroll, 1993; Cattell, 1963; McGrew, 2009; McGrew et al., 2023), although debates continue regarding the specifics of general ability (Kovacs & Conway, 2016).

Our understanding of human cognition, including general intelligence, is based on a very productive psychometric research program spanning more than a century, as well as decades of research on the underlying cognitive mechanisms and processes (e.g., working memory, processing speed) (Carpenter et al., 1990; Hunt et al., 1975) and more recently studies of the underlying brain networks (Barbey, 2018; Jung & Haier, 2007; Penke et al., 2012) and associated genetic correlates (Gargus & Haier, 2025; Loughnan et al., 2023). The corresponding research has been largely driven by the methodologies available to study cognition and not by a broader theoretical perspective. Tinbergen’s (1963) four questions about the nature of biological traits will provide such a multidimensional theoretical perspective on human cognition and in doing so provide avenues for future empirical studies. Bateson and Laland (2013) summarized these four questions:

“These problems can be expressed as four questions about any feature of an organism: what is it for? How did it develop during the lifetime of the individual? How did it evolve over the history of the species? And, how does it work?” (Bateson & Laland, 2013, p. 712).

The questions in effect state that a full understanding of the trait or traits in question only emerges when these are answered and when the relations among them are integrated. Of course, the trait or traits of interest need to first be identified. I focus on fluid intelligence, or the ability to adapt and problem solve in novel contexts, and the core supporting frontoparietal brain network, as well as on the default mode network that enables the generation of self-referential mental models that can be used in problem solving. The focus is on distinct brain networks, because from this perspective g – brain mechanisms common to all forms of perception and cognition – is potentially just a summary variable that captures individual differences at multiple levels of analysis (e.g., network integrity, synaptic plasticity). If so, then different individuals could achieve similar g scores with somewhat different constellations of strengths and weaknesses at the different levels described in Section 2. In any case, some of the basic issues are outlined in Table 1. I cannot address all of them here but elaborate on a few to illustrate the utility of the evolutionary framing.

2. Evolutionary Perspective

2.1. How Did Human Cognition Evolve and What is Human Cognition For?

Evolution will favor traits that are partially heritable and enhance survival and reproductive prospects across generations. The associated selection pressures are often conceptualized as ecological or social. Ecological pressures include weather patterns that can affect food availability, as well as the effects of predators, prey, and parasites on survival prospects. The influence of weather patterns on food availability and the associated evolutionary change in the size and structure of the beaks – which influence the types of foods that can be eaten – of Darwin’s finches on the Galápagos islands have been extensively documented (Grant & Grant, 2014) and provide solid empirical support for Darwin’s (1859) mechanisms of natural selection. Social pressures involve competition among members of the same species for social influence and for access to and control of resources that are important in their ecology (Geary, 2005). Any heritable trait that facilitates this competition will evolve in the same way that the beaks of Darwin’s finches evolve (Mayr, 1974; West-Eberhard, 1983). West-Eberhard referred to these dynamics as social selection, which often includes cooperation with others to better help individuals compete for resource control or social influence. Sexual selection – intrasexual competition for social dominance and intersexual mate choices – is a subset of social selection and a potent driver of evolutionary change (Andersson, 1994; Darwin, 1871; Geary, 2021).

Ecological and social pressures are not mutually exclusive and the relative importance of one or the other likely varies across evolutionary time. Both classes of selection pressure have been proposed as influencing the evolution of human cognitive abilities. The common theme across proposals is the adaptive advantages of foresight, planning, and the ability to cope with social and ecological change and novelty (Alexander, 1989; Ash & Gallup, 2007; Bailey & Geary, 2009; Flinn et al., 2005; Geary, 2005; Kanazawa, 2004; Kaplan et al., 2000; Potts, 1998). The models thus primarily focus on fluid intelligence rather than g per se. Figure 1 integrates the core of these models in ways consistent with Cattell’s (1963) original insight that the current function of fluid intelligence is to cope with novelty. The straightforward extension here is that the advantages to coping with social and ecological variability or novelty also drove the evolution of the supporting brain and cognitive systems, even if many of the novel conditions today (e.g., schooling) are different than those that drove the evolution of these systems. All this tells us, however, is that independently developed evolutionary models and Cattell’s proposal converge on the critical importance of brain and cognitive systems that can cope with novelty and change, but this does not inform us about the pressures that resulted in the evolutionary elaboration of these systems.

One way to make inferences about these pressures is to explore the most likely contributors to the three-fold increase in brain size over the past 4 million years of hominin evolution and the accelerated pace of enlargement since the emergence of the genus Homo about 2 million years ago (Antón et al., 2014). Here, I assume that the moderate correlation between brain size and fluid intelligence in living humans (Deary et al., 2022) holds during human evolution (Peñaherrera-Aguirre et al., 2023), that is, that fluid abilities supported in part by the frontoparietal network (FPN) and use of mental models supported by the default mode network (DMN) increased with gains in overall brain size – in fact, they disproportionately increased as elaborated in Section 2.2.

One proposal is that ecological change was the primary driver of the evolutionary enlargement of hominin brain, including deforestation and increases in savannah in sub-Saharan Africa before the emergence of Homo (Vrba, 1995). The proposal, however, is inconsistent with the finding that other primates living in these same regions did not show a comparable change in brain size (Elton et al., 2001). Moreover, Stibel (2025) found no relation between hominin brain size and glaciation periods during the Pleistocene, except for changes during the past 100,000 years. The largest of these changes – decrease in brain size – occurred with deglaciation about 17,000 years ago, with more recent climate fluctuations being unrelated to brain size (Stibel, 2023). Stibel concluded that “climate appears to account for only a small amount of the variation in brain size evolutionarily” (Stibel, 2023, p. 104). Overall, it appears that there was something specific to our Australopithecine and especially Homo ancestors that drove brain expansion. This specific something was potentially a with-species arms race whereby improvements in tool technologies and other innovations (Foley & Lahr, 1997), such as cooking which increases the calories and nutrients available in food (Aiello & Wheeler, 1995), resulted in gains in the ability to extract resources from the ecology and reduce predatory threats. Alexander (1989) called this ‘ecological dominance’.

“the ecological dominance of evolving humans diminished the effects of ‘extrinsic’ forces of natural selection such that within-species competition became the principle ‘hostile force of nature’ guiding the long-term evolution of behavioral capacities, traits, and tendencies”

(Alexander, 1989, p. 458).

Increases in food extraction technologies and cooking would have increased the carrying capacity of the ecology and thus provided the additional calories needed to expand brain size. The consistent use of hearths for cooking emerged about 400,000 years ago and is indeed associated with gains in brain size (Dunbar, 2025; Roebroeks & Villa, 2011). These gains, however, would not have emerged unless the advantages of increased size and associated cognitive gains resulted in survival or reproductive payoffs. Increases in carrying capacity are generally associated with population expansions and eventually heightened social competition as per capita resource availability decreases (Mac Arthur & Wilson, 1967). In other words, these documented gains in technology and innovation in our ancestors likely resulted in simultaneous reductions in energetic constraints on brain expansion and eventual increases in the intensity of social competition. The result was the perfect storm for the eventual emergence of an unprecedented within-species arms race, as illustrated in the top and rightmost ovals of Figure 1.

Geary (2005) argued that intensifying social competition modified Darwin and Wallace’s (1858, p. 54) conceptualization of natural selection as a “struggle for existence” to become in addition a struggle with other human beings for control of the resources that support life and allow one to reproduce (p. 60). The eventual result of this struggle for control of diminishing per capita resources would be a population crash, as was described by Malthus (1798) for Europe and parts of Asia and Hamilton and Walker (2018) for hunter-gatherer populations. The crash in turn would increase the per capita availability of resources and trigger another cycle of population expansion and later contraction. A critical feature of these crashes is that they disproportionately affected lower-status individuals and their families (Brändström, 1997; United Nations, 1985). An example is provided by demographic records from 18th century Berlin, whereby Schultz (1991) found a strong correlation (r = .74) between infant and child mortality rates and family socioeconomic status (SES, based on a combination of income, education, and occupation). Infant mortality rates were about 10% for aristocrats but more than 40% for laborers and unskilled technicians. “A senior official of the welfare authorities (Armenbehörde) observed in 1769 that among the poor weavers of Friedrichstadt 75 out of every 100 children borne died before they reached [the age of 12 years]” (Schultz, 1991, p. 243).

Repeating cycles of population expansion and contraction will accelerate evolutionary selection and favor traits that provide a competitive advantage over others in terms of social influence and control of culturally important resources (Geary, 2021). There are probably many such traits (e.g., healthy immune system), and fluid intelligence was likely one of them (Geary, 2005). As shown in Figure 1, my suggestion is that fluid intelligence and related competencies (e.g., for creativity and associated DMN brain systems described below) facilitated the creation of novel technologies, social strategies, and patterns of social organization that resulted in competitive advantage. Gains in fluid and related abilities then increased the potential of the remaining population (after the crash) to make further technological and other gains. We cannot directly study the associated social dynamics among early species of Homo or early modern humans, but evidence for this proposal is found in the historical record.

An example is provided by the development of large-scale agriculture, which produces a lower-quality diet than hunting and gathering, but with more food overall that reduces risk of famine and supports the formation of larger social groups; larger groups have a competitive advantage over smaller ones (Clark, 2007; Geary, 2021). The additional calories could be stored as grain reserves or in livestock that created a source of wealth for the taking (Hirschfeld, 2015; Turchin, 2009). And in many areas of the world, the wealth was taken through raids by mobile nomadic groups (i.e., pastoralists). The theft of agricultural communities’ resources created benefits for the formation of larger communities that in turn was countered by smaller nomadic groups uniting into larger ones that increased their competitiveness.

This type of warfare cycle emerged in many parts of the world and was associated with incremental advances in social organization (e.g., larger villages, early cities), military strategy and technology (e.g., chariot), and eventually leading to the formation of empires (Currie et al., 2020; Hermann et al., 2020; Turchin et al., 2013). The historical record and the implied intensity of social competition (especially for men; see Geary, 2021) is supported by numerous population genetic studies showing the replacement of one human population by another in all parts of the world (Zeng et al., 2018; Zerjal et al., 2003). In a recent review of ancient DNA patterns and their implications for understanding prehistorical social dynamics, Liu et al. (2021) note:

After the [Last Glacial Maximum, about 20,000 years ago], a warmer and more stable climate emerged, and human population dynamics from this time are characterized by a series of rapid expansions, migrations, interactions, and replacements. (p. 481).

These and related studies indicate that population interactions typically resulted in admixture (i.e., cross breeding) or the replacement of one group by another. The latter often involved the men of the new group replacing the men of the original group and reproducing with the women of the original group (Liu et al., 2021; Speidel et al., 2021). Zeng et al. (2018), for instance, found evidence for an extreme contraction of men’s genetic variability 5,000 to 7,000 years ago from Africa to Europe to East Asia, with little change in women’s genetic variability. Genetically, the population size of women was 17 times larger than that of men, indicating violence eliminated much of the male population during this epoch. These conflicts along with disease and famine are associated with population boom and bust cycles (Hamilton & Walker, 2018; Malthus, 1798), and consistent with a long-term within-species arms race that would favor traits that provided social-competitive advantages (Scheidel, 2017). These advantages would include the functional competencies of the FPN and DMN.

2.1.1. What’s Human Cognition Good For Now?

As noted in Table 1, the evolved functions of the systems that enable adaptation to novelty and change are also useful for adapting for the evolutionarily novel features of the modern world. The most important of these include schooling and the modern workplace (Geary, 2005; Kanazawa, 2004). These are cultural innovations that require adapting basic or primary brain and cognitive systems, such as the language network, for learning secondary or evolutionarily novel academic competencies, such as reading, that are important for day-to-day life in the modern world (Geary, 2024). The same basic plasticity and problem-solving abilities that emerged through the evolutionary arms race likely contribute to the ability to learn these academic skills and knowledge. Indeed, fluid abilities and supporting cognitive mechanisms, including executive functions, are the best predictors of academic learning and work performance (Hunter & Schmidt, 1996; Kriegbaum et al., 2018; Lubinski, 2000; Walberg, 1984; Wolfram, 2023). In keeping with the argument that these systems evolved to cope with variation and novelty, the more complex and novel the academic domain or work requirements, the more important these systems become.

In a broader sense, these cultural innovations and academic competencies are part of the longer-term trend toward organizing into larger social groups and generating new strategies to stay competitive relative to other groups. Indeed, formal academic instruction developed (or at least increased in frequency) with the emergence of early empires and dates back at least 5,000 years (Eskelson, 2020). In these contexts, formal education was used to train a small number of scribes in literacy and numeracy, who in turn supported the bureaucratic management of these societies and feted the accomplishments of the society’s elites. As the complexity of societies increased over time, schools expanded, albeit fitfully, in the covered academic content and in the student populations they served. For instance, universal education emerged in Europe over the past 400 years and, in keeping with the social competition thesis, was focused on increasing national unity and military and economic competitiveness (Goldin, 1999; Ramirez & Boli, 1987). The same is true for many modern workplaces whereby private companies organize the activities of people to better compete against rival companies.

In short, success in modern workplaces as well as in school and likely in less formal contexts (e.g., learning tool construction) in premodern societies enhances individuals’ relative status. As described above (Section 2.1), gains in social status reduced mortality risks in historical contexts and thus selected for traits that enhanced social mobility, including functions of the FPN. A group ethos that supports the education of its population enhances the competitiveness of the group vis-a-vie other groups (Gust et al., 2024; Rindermann, 2018). The latter is important in the context of the population genetic data showing that the replacement of one group by another was a common feature of human social dynamics.

2.2. How Does Human Cognition Work?

A core issue concerns the brain and cognitive mechanisms that supported the proposed evolutionary arms race. One key mechanism is the use of cognitive control networks to construct mental models that can be used to generate and explicitly evaluate potential solutions to changing social dynamics, variation in ecological conditions, or to generally solve novel problems (Alexander, 1989; Geary, 2005; Humphrey, 1976). These mental models allow people to think about things that have not happened and generate various potential outcomes and solutions to novel problems. At the cognitive level, these models are supported by well-known domain-general abilities, such as executive functions, along with the use of the visuospatial and language systems to populate the models with content.

There are multiple brain networks that support engagement with the world and various problem-solving activities (J. D. Power et al., 2011; Yeo et al., 2011). The six core cognitive control networks identified by Menon and D’Esposito (2022) are the most relevant to an evolutionary arms race. An extensive discussion of these networks is not possible here, but a few examples will illustrate the utility of the approach, focusing on the DMN and the FPN. These networks support internally and externally focused problem solving, respectively, and both are related to either fluid problem solving or more general cognitive abilities (i.e., performance across cognitive domains) (Bruner, 2024; Jung & Haier, 2007; Yadav & Purushotham, 2025). If these networks have evolved in unique ways during human evolution, then at least some aspects of these networks should be relatively enhanced in humans relative to chimpanzees and monkeys. An understanding of these comparative differences in brain networks and the underlying functions will provide unique insights into the pressures that drove human brain evolution and another opportunity to test the social competition model.

2.2.1. Default mode network

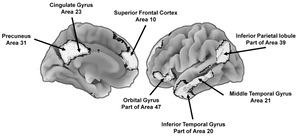

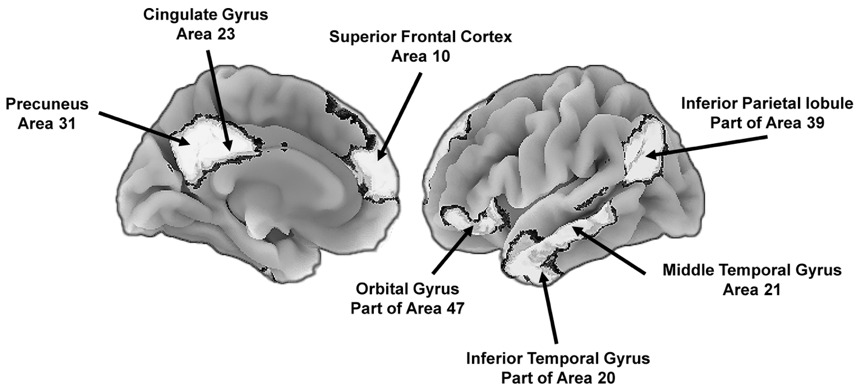

The DMN (Figure 2) is important because many of the associated functions are consistent with intense social selection pressures and a within-species evolutionary arms race. Relative to overall brain size, the human DMN is disproportionately larger than that of chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes), macaque monkeys (genus Macaca), and potentially Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis), and genes that have undergone recent evolutionary selection are disproportionately expressed in several areas that compose this network (Balzeau et al., 2012; Bruner, 2018; Buckner & DiNicola, 2019; Wei et al., 2019). These patterns indicate the DMN is an evolutionary hotspot. The associated changes include better integration of the anterior and posterior regions of the network that in turn supports the ability to generate top-down mental models (Garin et al., 2022), and better integration of current activities (e.g., a conversation) with self-relevant beliefs (Yeshurun et al., 2021). For instance, the architecture of this network in evolutionarily distant primate relatives (e.g., lemurs, genus Lemuroidea) does not include mechanisms that would support the top-down generation of a human-like mental model, although chimpanzees may have rudimentary competencies in this area, but this remains to be substantiated.

The DMN is primarily active during relaxed states and, among other things, results in “a self-centered predictive model of the world” (Raichle, 2015, p. 443). The precuneus (Figure 2) is a core part of the DMN and has shown substantive enlargement since the emergence of H. sapiens (Bruner, 2024; Bruner et al., 2017) and is one of the most metabolically demanding regions of the human brain (Gusnard & Raichle, 2001). The precuneus contributes to feelings of agency, self-awareness, episodic (personal) memories, and thinking about the world in self-referential ways (Cavanna & Trimble, 2006; Rugg & Vilberg, 2013). The prefrontal components of the network contribute to top-down self-reflection, goal-directed self-evaluations, retrieval of episodic memories, and thinking about other people (Davey et al., 2016; Konu et al., 2020; Mancuso et al., 2022; Smallwood et al., 2021). The content of these models is consistent social pressures contributing to the evolutionary elaboration of the DMN.

“The content of self-generated thoughts suggests that they serve an adaptive purpose by allowing individuals to prepare for upcoming events, form a sense of self-identity and continuity across time, and navigate the social world. On average, adults tend to rate their thoughts as goal oriented and personally significant, yet thoughts also commonly involve other people.” (Andrews-Hanna et al., 2014, p. 32).

Mental time travel is one critical function of the DMN and includes the ability to self-construct mental models of current and potential future states and to use problem solving, with contributions from FPN, to generate and rehearse strategies that could reduce the difference between these states (Menon, 2023; Østby et al., 2012; Suddendorf & Corballis, 2007), which provides a critical advantage in the context of social competition (Alexander, 1989; Geary, 2005). This perspective aligns nicely with Oeberst and Imhoff’s (2023) proposal that humans’ most fundamental cognitive bias is the implicit or sometimes explicit assumption that their self-referential view of the world is fundamentally correct and what is correct for them is also correct for others. The only added assumption here is that people’s view of the world is generally aligned with their self-interests, including the future states they wish to obtain. The future that people think about typically involves gains in social influence and status, as well as enhanced access to culturally important resources (e.g., money) relative to their current state. The evolutionary advantages were described in section 2.1, whereby relative (to other people) gains in status and resource control were associated with enhanced survival and reproductive prospects in historical contexts and in many developing nations today. The salience of relative gains would provide evolutionary advantages to social-comparative processes (Festinger, 1954) that result in a focus on relative status and control, not simply the acquisition of sufficient resources for survival and reproduction (Alexander, 1989; Flinn et al., 2005; Geary, 2005).

The DMN also includes areas of the temporal cortex that are associated with social cognitions, such as theory of mind, and semantic and conceptual knowledge. The latter include knowledge about the self in relation to other people (e.g., relative level of extraversion), an understanding of how other people perceive you, and an understanding of ones’ internal states (e.g., emotional) (Xia et al., 2025). These are important components of self-referential mental models including the ability to simulate how others will react to different arguments or attempts to persuade them or influence their behavior in other ways. Sensitivity to and the ability to reflect on emotional states provides advantages in understanding social dynamics, and awareness of ones’ strengths and weaknesses provides advantages in social niche construction, that is, focusing on skill development in areas in which one has comparative advantages (Geary & Xu, 2022; Leary & Buttermore, 2003).

These competencies overlap with parts of the controlled semantic cognition system in the temporal lobe and parts of the prefrontal cortex (Binder et al., 2009; Lambon Ralph et al., 2017), such as the inferior frontal gyrus, that are also integrated with the FPN (Fedorenko et al., 2013; Menon & D’Esposito, 2022). Many areas of this semantic cognition network are evolutionary hotspots (Lambon Ralph et al., 2017) and critically are associated with human’s unique ability to form abstract generalizable concepts about the social, biological, and physical worlds, insights that elude other species including chimpanzees (Penn et al., 2008; Povinelli, 2000).

The DMN and the semantic cognition system are also important for visuospatial (e.g., navigation) and visual-manual (e.g., as related to tool use) behavior and imagery (Cavanna & Trimble, 2006), as well as forming conceptual representations of common features of the physical word, such as its three-dimensional structure, and presumably the biological world. The fusion of abstract representations of the world with the ability to generate mental models is likely a core aspect of the ability to innovate and discover in science, technology, and the arts (Geary, 2007, 2024; Gotlieb et al., 2019), and part of the evolutionary model shown in Figure 1. Indeed, the mind wandering component of the DMN has been implicated in creative cognition, such as making associations between remote phenomena (Andrews-Hanna et al., 2017; Konu et al., 2020; Kühn et al., 2014; Marron et al., 2018). The contribution to innovation appears to result, in part, from the dynamic interaction between two sub-systems of the DMN, one that generates images, word associations, and mental time travel (more posterior areas) and one that involves a top-down control and evaluation of these thoughts and images (more anterior areas). This is experienced as internally focused attention with a somewhat constrained train of images and thoughts focused on goal achievement. The process is illustrated by the descriptions of the problem-solving approaches of some innovators. In response to a query by Hadamard (1945) as to how he approached scientific questions, Einstein replied:

The words of the language as they are written or spoken, do not seem to play any role in my mechanism of thought. The psychical entities which seem to serve as elements in thought are certain signs and more or less clear images which can be “voluntarily” reproduced and combined. … There is, of course, a certain connection between those elements and relevant logical concepts (Hadamard, 1945, p. 142).

Hadamard (1945, p. 143) also noted that Einstein “refers to a narrowness of consciousness,” which appears to have referred to sustained attention and the inhibition of distracting information, which likely involved the cognitive control networks that maintain attentional focus (Menon & D’Esposito, 2022). Einstein’s accomplishments are, of course, unusual, but his descriptions of how he achieved some of his insights are of interest. This is because they are consistent with an attention-driven use of internally generated mental simulations that involve a top-down engagement of basic visuospatial abilities. Stated differently, it appears that Einstein intentionally engaged the DMN to form mental simulations that, in his case, used visuospatial representations (e.g., moving images) as part of his problem solving.

It might then be argued that the evolution of the DMN was driven by ecological rather than social selection pressures, given the importance of visual imagery and visual-manual abilities to tool construction and use (Hegarty, 2004). Indeed, gains in technology are a defining feature of human evolution since the emergence of the genus Homo and likely contributed to human’s achievement of ecological dominance (Foley & Lahr, 1997). As shown in the center section of Figure 1, technological advances are at least in part motivated by and enhanced between-group social competition. Even in many traditional societies today, many tools, such as clubs and bows-and-arrows, are constructed to facilitate the often deadly between-group male-on-male competition (Hrnčíř, 2023) which has well-documented reproductive consequences (Geary, 2021). More broadly, warfare often contributes to the refinement of existing technologies or the emergence of new ones, along with associated social innovations, such as logistics to support large armies (W. W. E. Lee, 2016), although many of these innovations are likely driven by DMN and FPN interactions.

2.2.2. Frontoparietal network

The FPN supports working memory and controlled problem-solving and is often identified as undergirding fluid abilities (Barbey, 2018; Fedorenko et al., 2013; Jung & Haier, 2007; Santarnecchi et al., 2017). Although not a focus here, it should be noted that the salience network, including the anterior insular (AI) and dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC) may be critical to the goal-related orchestration of cognitive control networks during complex problem solving (Uddin, 2015), including shifting between DMN and FPN engagement during problem solving. These networks are integrated with the cingulo-opercular network that supports a sustained level of alertness and focus, as described by Einstein, that is often needed for goal achievement (Coste & Kleinschmidt, 2016). The combination supports top-down problem solving, often called executive attention (Miyake & Friedman, 2012; Witt et al., 2021; Yeo et al., 2011).

Comparative studies suggest substantive evolutionary change in these executive functions and the underlying brain systems. Behavioral studies of various primate species indicate strong attentional and problem-solving competencies, relative to many non-primates, but at about the level found in preschool and kindergarten children (Beran et al., 2016; Posner, 2023); Peñaherrera-Aguirre et al.‘s (2023) analysis suggests that gains in executive functions emerged gradually during hominin evolution. The core of the cognitive control networks is more differentiated in primates than in other mammals and more differentiated in humans than in other primates (Preuss & Wise, 2022). Many of the brain areas that support these networks are disproportionately larger in humans than would be expected based on overall brain size (Wei et al., 2019). As with the DMN, there appears to have been evolutionary modifications of the white matter connectivity between these prefrontal regions and the attentional regions in the parietal cortex (Hecht et al., 2015). The result would be an enhancement of humans’ ability to use cognitive control networks in a top-down fashion in the service of complex, multi-step problem solving.

These evolutionary changes include two core components of the salience network, the ACC and AI, as well as components of the FPN. These areas are more highly integrated in humans than in other primates, which would enhance the ability to switch between networks during problem solving (Molnar-Szakacs & Uddin, 2022; Posner & Rothbart, 2009; Uddin, 2015). The salience network is engaged when goal achievement requires dealing with novelty or conflict in social or non-social contexts (Burgos-Robles et al., 2019; Monosov et al., 2020). For people, choice or conflict situations often result in an attentional shift to the associated information and activation of the FPN (Botvinick et al., 2001). Engagement of the latter and other integrated cognitive control networks, such as the cingulo-opercular network, enables a longer period of sustained attention relative to other primates and supports prolonged engagement in explicit step-by-step problem-solving.

Engagement of these explicit problem-solving networks, especially the FPN, typically deactivates the DMN. There is, however, an area of the precuneus that is integrated with the cognitive control networks, is active with an external focus, and appears to be involved in the integration of previous knowledge with external demands (Dadario & Sughrue, 2023). There also appears to be sequential interactions between the DMN and FPN when attempting to generate novel or creative solutions to current or anticipated future problems (Gotlieb et al., 2019). The DMN contributes to internally generating mental models that include alternative solutions to problems, especially social ones, and connecting disparate ideas, while the FPN contributes to the implementation and evaluation of potential solutions. The flexible switching is controlled through the salience network (Andrews-Hanna et al., 2014; Heinonen et al., 2016), and the combination is particularly important for the evaluation of internally generated information (Beaty et al., 2015). These integrated functions explain the cross-species differences in the behavioral-attention and problem-solving studies and again point to evolutionary pressures that were unique to our ancestors.

2.2.3. Global Network Functions

Individual differences in DMN and FPN functioning are predicted to be associated with the proposed evolved functions of the networks, including variation in traits that contribute to social competitiveness. The functions would include self-awareness, mental time travel, and aspects of social cognition for the DMN and explicit step-by-step problem solving for the FPN. Similarly, injury and disease that compromise any level of functioning of these networks are predicted to have the same effects. In other words, degradations in DMN and FPN functioning provide insights into the selection pressures and proximate advantages that contributed to their evolution: Degradation could also manifest as difficulties in switching between networks in the service of coping with novel or variable conditions (Fotiadis et al., 2024).

As predicted, disruptions to functional connectivity among DMN hubs (e.g., due to use of psychedelics) are associated with a reduced ability to engage in mental time travel, a diminished sense of self, and poor differentiation between the self and others (Northoff et al., 2025). Poor functional connectivity within the DMN or damage to the network is associated with risk of schizophrenia, a reduced capacity to think about the future, and difficulties with autobiographical memory (Philippi et al., 2015; Xia et al., 2025; Ye et al., 2023). These deficits are associated with social and occupational difficulties and often with downward social mobility (R. A. Power et al., 2013; Wheeler et al., 1997). Gardner et al. (2022) found that genetic mutation loads related in part to lower fluid intelligence and severe psychiatric disorders (e.g., schizophrenia) were associated with increased odds of being childless for men and this appears to have contributed to the evolutionary reduction in genetic loads that can compromise FPN and likely DMN functioning.

At the same time, relatives of individuals with disorders that can compromise aspects of DMN functioning, such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, are overrepresented in creative professions (Kyaga et al., 2011; Parnas et al., 2019), suggesting cost-benefit trade-offs to the expression of the underlying genes and a mechanism that would maintain these genes in the population. These patterns are consistent with the proposed relations between the DMN and FPN functions in the creation of cultural and social innovations in the context of a within-species arms race (Fig. 1) (Azarias et al., 2025; Beaty et al., 2016; Luchini et al., 2025; Shofty et al., 2022); of course, creative cognition can also be used for other purposes, such as creation of music and art, but these too have a social-competitive component to them (Geary et al., 2021; Winegard et al., 2018).

Along with contributions to creative cognition, individual differences in the integrity and efficiency of the FPN predict individual differences in fluid intelligence (Barbey, 2018; Jung & Haier, 2007; Qiu et al., 2025; Santarnecchi et al., 2017) that in turn enhances social competitiveness (Bratsberg et al., 2025; Geary, 2005; Lubinski, 2025). In modern contexts this is manifested as individual differences in educational and occupational status and through this income (Pesta et al., 2023; Schmidt & Hunter, 1998). Higher fluid and related abilities are also related to more general social functioning, such as lower delinquency and arrest rates (Herrnstein & Murray, 1994; Pesta et al., 2023). The importance of these relations to the proposed evolutionary model is not fully evident in modern contexts but is clear in contexts with higher child mortality rates.

As mentioned in Section 2.1, families with higher social and occupational status have consistently lower child mortality risks in developing nations today and in Western nations historically (Brändström, 1997; Khadka et al., 2015; Reid, 1997; Schultz, 1991; Sonego et al., 2015; Strenze, 2007). The same pattern emerged in Song et al.'s (2015) analysis of lineage extinction during the Chinese Qing dynasty (1644-1911). The analysis included 20,000 patrilineages and revealed that higher-status men had somewhat higher reproductive success than lower-status men, but more critically they had a much lower chance of lineage extinction over the next six generations. Extinction risk was independent of the number of children born in each generation, indicating that lineage continuance was not simply due to higher-status men having more children. In addition, these children and their descendants were less likely to die than those of lower-status men. The cause of the extinctions was not assessed, but H. Lee (2018) documents numerous epidemics, famines, internal wars, and invasions during the Qing dynasty and the preceding Ming dynasty that are typically associated with population crashes that disproportionately increase mortality rates among lower-status families. The point is that there has often been positive selection for traits, including fluid abilities, that influence status striving and achievement, in keeping with a within-species arms race.

From this perspective, disruption of or damage to the FPN should compromise competitive abilities in modern contexts (Mah et al., 2004). Although deficits in social decision making and cognition are typically associated with damage to the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (Lockwood et al., 2024; Tranel et al., 2007), damage to the FPN can disrupt social inference making and self-reflections when these engage working memory and cognitive control networks (Mah et al., 2004). Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) typically precedes the onset of Alzheimer’s disease and is associated with changes in functional and structural connectivity within the FPN (and DMN) and between the FPN and other networks (Yang et al., 2023). These changes and changes at the cellular level are associated with declines in working memory, episodic memory, emotion regulation and other competencies that in turn are associated with compromises to social and occupational functioning (Bora & Yener, 2017; Lindbergh et al., 2016). Declines in occupational functioning are found even for working-aging adults with early onset MCI, with compromises to executive functions being a core contributing factor (Sakata & Okumura, 2017; Silvaggi et al., 2020).

From an individual differences perspective, lower SES adults have a hypoactive engagement of FPN and broader cognitive control networks and hyperactive engagement of reward networks during problem solving compared to their higher SES peers (Yaple & Yu, 2020). These differences would influence social and occupational functioning, but cause-effect cannot be determined from these types of studies, that is, whether individuals with this profile are downwardly mobile, whether growing up in a lower SES environment contributes to these differences, or bidirectional influences (Farah, 2017). Whatever case, the overall pattern is consistent with the hypothesis that disruption of the FPN will compromise social-competitive cognitive abilities (more on this in Section 2.3).

2.2.4. Cellular and Intracellular Functions

As noted in Table 1, a complete evolutionary analysis requires an understanding of the most basic biological functions that support the brain networks that undergird complex human cognition. The overall functioning of these large-scale networks will be influenced by structural, white-matter connectivity between the dispersed brain regions that compose the network, as well as by mechanisms that influence efficient within network connectivity, dynamics within and between individual neurons and supporting cells, underlying molecular processes, and by the efficiency of intracellular processes (Alberini, 2025; Luo, 2021; Qiu et al., 2025). These different mechanisms are coordinated and maintained in part through experience-driven activation of these large-scale networks, as elaborated in Section 2.2.5, and by spontaneous network activity. Network activation results in grey (e.g., changes in neurons or supporting cells) and white matter (e.g., enhanced myelinization) changes that support the functional competencies of the network, as well as learning, memory, and network plasticity (Zatorre et al., 2012). These would include episodic memory that is a central function of the DMN and learned solutions to problems resulting from engagement of the FPN and other cognitive control networks.

As an example of the complexity of these systems, consider that there are numerous microcircuits within discrete areas that compose large scale networks (Luhmann, 2023; Luo, 2021; J. D. Power et al., 2011). These are small networks of adjacent neurons that receive specific inputs and generate specific outputs from and to other microcircuits or larger-scale cell ensembles. Moreover, cells within microcircuits can form bioelectrical patterns (e.g., through shared ions) that can be modified (e.g., changing cell membrane potentials) in ways that represent a form of shared memory (Cervera et al., 2023). Whatever the specific mechanisms, distributed microcircuits enable efficient processing of distinct pieces of information and massive parallel processing of related information.

There are many ways in which microcircuits can be configured and interconnected, and this enables the evolution and development of specialized architectures for specific functions. This is analogous to basic building blocks that can be used to construct different subunits that can be put together in different ways to create different structures from the same basic materials. These combinations of microcircuits (or individual neurons) can form dynamically engaged larger-scale neuronal assemblies that are coactivated during a specific task and with repeated coactivation potentially modifying patterns of excitatory and inhibitory connections that in turn reflect learning and memory (Holtmaat & Caroni, 2016). Qiu et al. (2025) found that distributed areas of the FPN showed enhanced white matter connectivity consistent with elaborated microcircuits. Hart and Huk (2020) found that working memory maintenance in the macaque FPN involved synchronized activity between frontal and parietal regions, as well as persistent activity of microcircuits within these areas.

The development and functioning of such microcircuits and the formation and consolidation of larger-scale neural assemblies are dependent on multiple lower-level processes. These include intra- and inter-cellular and molecular changes that support synaptic plasticity and memory consolidation through structural (e.g., spine formation on dendrites) and synaptic changes that define long-term potentiation, that is, experience-driven long-lasting strengthening of the efficiency of synaptic transmissions (Csermely et al., 2020; Goto, 2022). This includes strengthening of pre-existing synaptic connections (functional synaptic plasticity), and the formation of new connections and elimination of unused ones (structural plasticity) (Holtmaat & Caroni, 2016). These changes are associated with intracellular changes, such as upregulation of micro-RNA (ribonucleic acid), that alter patterns of gene expression and cell functions (Alberini, 2025).

The key point is that the functional capabilities of any complex brain network, including DMN and FPN, requires the orchestrated activities at many levels of analysis from intracellular molecular mechanisms to the development and integrity of long-range white matter connectivity between core hubs of the network. To further complicate matters, the functioning of all these systems is dependent on intracellular energy availability, which largely comes from ATP (adenosine triphosphate) production in the electron transport chain within mitochondria (Killeen et al., 2016; Kuzawa et al., 2014; Magistretti & Allaman, 2015; Zhu et al., 2012). Energy production is a limiting factor on brain evolution, development, and functioning and influences trade-offs between performance and energy conservation (Bullmore & Sporns, 2012); as noted in Section 2.1, cooking and likely parallel gains in hunting efficiency during human evolution released energy constraints on brain evolution and functioning (Aiello & Wheeler, 1995). Mosharov et al. (2025) mapped mitochondrial density and energy producing capacity in the human brain and found that these were enhanced in regions of recently expanded (evolutionarily) complex brain networks, including FPN. In a small-scale study (thus in need of replication), Shatalina et al. (2024) found that individual differences in mitochondrial density in FPN areas, among others, was correlated with individual differences on various cognition measures.

Energy disruptions due, for instance, to nutritional stressors or toxin exposure can compromise the development and functioning of many brain mechanisms, but these should be especially noticeable for the most energy demanding systems (Geary, 2017, 2018). Yang et al. (2023) found that cognitive declines associated with MCI are associated with disruptions to brain regions with the highest metabolic demands, which include core areas of the DMN and the FPN. Shatalina et al. (2025) found that individual differences in mitochondrial density in dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, an important component of FPN, was associated with individual differences in healthy adults’ performance on an executive functions task. Age-related declines in mitochondrial energy production would have a broad effect on the efficiency of all physical systems, especially energy-dependent ones like the brain (Lane, 2011). Reduced energy production would compromise brain functioning at multiple levels and, in theory, result in simultaneous declines across cognitive abilities, with more pronounced declines for higher-energy systems like the FPN and DMN (Geary, 2018). This provides a simple, mechanistic explanation for age-related cognitive declines across domains and the relation between declines in health and cognition (Deary et al., 2010; Geary, 2019; Raz & Daugherty, 2018)

2.2.5. Genetic Mechanisms

Gargus and Haier (2025) provide an excellent review of genetic mechanisms that are correlated with human cognition, especially the development and functioning of DMN and FPN. Thus, there is no need for an extensive review in this section, but there are a few points that should be highlighted. The most basic one is that genetic influences on complex human cognition are found at multiple levels from the organization of the DMN and FPN to synaptic and intracellular processes, as detailed by Gargus and Haier. One implication is that individual differences in g – factors common to all cognition not just DMN and FPN functions – will be influenced by multiple genetic and biological systems that are not completely overlapping. In this situation, individuals with similarly high levels of g might achieve this outcome through different patterns of strengths, such as high network integration in the FPN or high plasticity at lower levels, and thus through different constellations of genetic influences. We might then expect more than one pattern of genetic influence on g, as recently found by Woodley of Menie et al. (2025).

Gargus and Haier (2025) note potential genetic and evolutionary influences on DMN and FPN development and functioning, and a few of these merit elaboration. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified genetic correlates of educational attainment and intelligence and many of these overlap with human accelerated regions (HARs) associated with unique features of human brain development. These types of studies are important but should be interpreted with caution because the results are influenced by sample sizes and methods for separating cognitive from non-cognitive (e.g., conscientiousness) genetic contributions to intelligence-educational attainment are not fully developed (Hill et al., 2016, 2018).

At this point, the HARs associated with intelligence and educational outcomes appear to involve expanded neural proliferation and differentiation (Whalen & Pollard, 2022; Won et al., 2019), including in regions of the DMN and FPN (Wei et al., 2019). Recall, comparative studies indicate DMN and FPN have expanded during hominin evolution, including enhanced white matter connectivity between the prefrontal and parietal regions of these networks (Buckner & DiNicola, 2019; Garin et al., 2022; Posner, 2023). Wei et al. showed that HARs genes are highly expressed the DMN, FPN, and the ventral attentional network in humans, especially in the DMN. These genes appear to contribute to the enhanced development of the DMN in humans relative to chimpanzees (e.g., more grey matter in humans), and a subset of these genes predicts individual differences in human adult DMN functioning.

Enhanced white matter connectivity between anterior and posterior regions of complex brain networks, including DMN and FPN, is related to human pyramidal cells in cortical layer 3. These cells have exceptionally large dendritic networks that receive and integrate information from multiple other cortical regions and are critical to long-range network connectivity. Driessens et al. (2023) found that pyramidal cells were more abundant the middle temporal cortex, part of the DMN and the semantic cognition system (Lambon Ralph et al., 2017), than in nearby sensory cortex. The associated gene sets overlap genes correlated with educational attainment, intelligence, and HARs, in keeping with an evolutionary enhancement of humans’ conceptual learning abilities. Genetic influences on the activity of pyramidal cells include enhanced synaptic functions that support synaptic plasticity and the generation of fast and reliable action potentials. Degradation of these cells and long-range connectivity is associated with disruption of network functions and cognitive decline (Hof et al., 1990).

Expanded cortical networks increased the energy demands of the human brain, which consumes about 20% of adults’ basal energy demands and more than half of this energy during the years of peak post-natal brain development (Kuzawa et al., 2014). This places intracellular mitochondrial ATP energy production as a central lower level limiting mechanism for the development and functioning of complex brain networks and for specific cellular functions (Geary, 2018; Plomin et al., 1995; Thomas et al., 1998). The mitochondrial genome, however, includes only 37 genes and the functions of this energy-producing system are dependent on a combination of mitochondrial and nuclear genes, different combinations of which are important in different tissues and in different brain regions (Lane, 2011; Mosharov et al., 2025). This complexity makes the identification of genetic contributions to cellular energy production more difficult to detect than genetic contributions to other brain functions, such as synaptic plasticity. There is nevertheless some evidence for genetic influences on mitochondrial energy production as related to cognition, although much remains to be learned (Kohshour et al., 2023; Xu et al., 2025).

One way to detect these influences is to examine (postmortem) the relation between protein products of mitochondrial energy production (related to combinations of mitochondrial and nuclear genes) and cognitive performance. In one such study, Xu et al. (2025) examined gene expression patterns in prefrontal cortex for individuals who had been infected with COVID-19 and non-infected controls. The study was motivated by the finding that inflammatory and related responses associated with COVID-19 and other infections are often associated with post-infection cognitive deficits, such as poor executive functions, that can last months and sometimes longer (Monje & Iwasaki, 2022). Xu et al. found that individuals who had COVID-19 had upregulated expression of genes associated with immune responses, not surprisingly, and downregulated expression of genes (mitochondrial and nuclear) that influence mitochondrial energy production. Many of the downregulated genes are important for the functioning of the electron transport chain that produces ATP. Mastroeni et al. (2017) found that downregulation of nuclear genes related to ATP production was common in the hippocampus of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease. Wingo et al. (2019) examined gene expression in brain tissue by examining the corresponding proteins that predicted stable cognitive abilities in older adults as compared to their peers with age-typical cognitive declines. “The proteome-wide association study reveals that the proteins with increased abundance in cognitive stability were involved in mitochondrial activities and synaptic transmission…” (Wingo et al., 2019, p. 5).

In all, these patterns and those described by Gargus and Haier (2025) are consistent with studies showing that hominin evolution included enhanced network integration of DMN and FPN. The associated genetic mechanisms, unsurprisingly, involve systems at different levels, from enhanced pyramidal cells, greater synaptic plasticity, and gains in mitochondrial energy production. The key takeaway is that these specific mechanistic enhancements are part of a bigger picture that only makes sense in terms of the evolutionary benefits associated with enhanced functions of DMN, FPN, and other systems (e.g., semantic cognition system). These benefits have to be substantial given the energy costs of the human brain and the increased risk of extinction if the fuels that supply this energy diminish, such as in a famine (Stibel, 2025).

2.3. How Does Human Cognition Develop?

The incorporation of developmental issues into an evolutionary framework first involves uncovering how selection pressures can influence the timing of key developmental events (e.g., age of sexual maturation) or changes in length of key developmental periods (e.g., gestation length). Comparative or cross-species differences in key aspects of this life history development suggest different selection pressures, such as differences in diet, ecology, or intensity of social competition (Antón et al., 2014; Shea, 1983). Generally, slower development, larger brains, and longer lifespans go together in primates and suggest that slower development results in enhanced opportunities to learn or refine skills that are needed for survival and reproduction in adulthood. Exactly what needs to be learned during development varies across species and ranges from the complexities of finding high-quality foods (e.g., fruits) to the demands of social competition and learning from others (DeCasien et al., 2017; Street et al., 2017).

The second developmental issue concerns (for us) actual changes in brain development, including their relation to neural plasticity. At the most basic level, the realization of evolutionarily enhanced brain areas and networks is dependent on changes (e.g., in number of progenitor brain cells) during prenatal and postnatal development when the basic architecture of these networks is formed. As an example, Neubauer et al. (2018) examined evolutionary change in the pattern of brain shape comparing modern and early archaic humans to H. erectus and Neanderthals. The two latter species have brain shapes that are elongated, that is, the front-to-back distance is longer than in modern humans but the top-to-bottom distance is shorter. Early archaic humans older than 35,000 years ago had a shape in-between Neanderthals and modern humans. The current human shape emerged 10,000 to 35,000 years ago and includes expansion of parts of the parietal cortex, most likely including a key area of the DMN, that is, the precuneus. The current modern human brain shape emerges prenatally, indicating both relatively recent changes in brain evolution and early developmental processes contributing to these changes.

Associated developmental processes are driven by intrinsic factors (e.g., patterns of gene expression), termed the protomap hypothesis (Raichle, 2015), and activity-dependent extrinsic factors (Greenough et al., 1987), termed the protocortex hypothesis (O’Leary et al., 1994). During prenatal development, some areas of the human brain, including parts of the prefrontal cortex, show region-specific patterns of gene expression and specific genetic influences on the specialization of these areas, following the protomap hypothesis, and other regions become specialized based in part on patterns of input from other brain regions (e.g., thalamus), following the protocortex hypothesis (Bhaduri et al., 2021). The key point is that the basic structure of most mammalian brain regions emerges prenatally through patterns of region-specific processes and many of these systems become refined by activity patterns triggered by other regions (Cadwell et al., 2019). In a comparative study of brain development, Gómez-Robles et al. (2024) showed that aspects of prenatal brain development found in other primates occur during the early postnatal period for humans and that key markers of postnatal brain development occur at later ages for humans than other primates, including our ancestors. They suggested that one result is enhanced human neural plasticity, especially as related to myelinization and the development of white matter tracks.

More specifically, the DMN and FPN, along with other complex networks (e.g., salience network), show important development changes during the second and third trimester of fetal development and early postnatally as indicated by diffusion tensor imaging (DTI, for white matter tracks) and structural and resting state MRIs (Scheinost et al., 2024; Thomason, 2020). For instance, Turk et al. (2019) found that the basic architecture of the DMN emerged during the second and third trimester of fetal development, but with less integration in the FPN relative to adults. In a resting state MRI study, Sylvester et al. (2023) found that the whole brain connectivity patterns of neonates (n = 262) were highly similar (r = .65) to those of children (8 to 13 years of age) and adults (r = .64), but not as similar as between children and adults (r = .91). A similar pattern was found for specific networks, including DMN and FPN. Developmental change involved increasingly selective connectivity of anterior and posterior regions of the same network, stronger negative or anticorrelations between networks (e.g., between FPN and DMN), and pruning of short-range connections within circumscribed network areas. In short, the basic architecture of core brain networks is evident at birth and show adult-like connectivity patterns by late childhood or earlier, although structural changes continue through adolescence (e.g., Supekar et al., 2010; Thomason, 2020).

These functional and structural developmental changes result in windows of vulnerability to network development but also opportunities to adjust network dynamics to current conditions, in keeping with brain development being dependent in part on species-typical or experience-expectant exposure to the forms of social and ecological information that contributed to brain evolution (Greenough et al., 1987). Indeed, sensitivity to postnatal experiences is an important aspect of brain plasticity at multiple levels (e.g., synaptic connections, integration of brain networks) and can differ across species and brain regions (Bonfanti & Charvet, 2021). Plasticity is linked in part to brain maturation such that slower developing brains imply greater potential for the evolution of modifiable brain systems, although this will be tempered by genetic constraints and hormonal influences during puberty (Arnatkeviciute et al., 2021; Bonfanti & Charvet, 2021). The first of two broad issues is whether developmental experiences, such as deprivation, can compromise network development and associated competencies. The other is whether developmental experiences result in adaptive changes in network functioning and biases.

The first broad issue concerns the species-typical activities needed to ensure normal development of DMN and FPN functions, such as self-awareness, executive functions, and underlying mechanisms (e.g., synaptogenesis). Social experiences are an important component of species-expectant development. Social isolation during development is species atypical for most primates and associated with disrupted brain development at multiple levels, including in areas of the DMN, and with later social deficits (Bzdok & Dunbar, 2022; Xiong et al., 2023). A similar situation often emerges for infants who are institutionalized and spend part of their childhood in contexts, such as orphanages, that are associated with low levels of social and general cognitive stimulation, that is, they have species atypical developmental experiences. These children often have deficits in social cognition and behavior, as well as in executive functions (Julian, 2013).

In adolescence and adulthood, many of these individuals show grey and white matter deficits, especially in prefrontal cortex and DMN and FPN parietal areas (Gunnar & Bowen, 2021). Lewis et al. (2024) found that individuals who had been institutionalized and adopted before age 5 years showed broader FPN prefrontal and parietal activation during an executive functions task in adolescence than did their peers. Broader engagement, including poor deactivation of the DMN for early adopted individuals, suggests compensatory mechanisms, not better general functioning of these areas. Eluvathingal et al.'s (2006) DTI study suggested white matter deficits in parts of the DMN in children adopted from orphanages. Less severe forms of deprivation are associated with lower volume and cortical thickness in core FPN regions (McLaughlin et al., 2019). In all, these studies indicate that deviation from species-typical developmental experiences, including social and cognitive deprivation, can compromise the formation of large-scale brain networks, but much remains to be learned about how these compromises vary with timing, duration, and intensity of these atypical experiences.

The effects of less extreme levels of deprivation can be estimated by comparing children who grow up in lower SES families to their peers that grow up in higher status families. The family differences are thought to result from less cognitive stimulation and higher levels of stressor exposure (e.g., related to financial issues) for children in lower status families. The proposal is that growing up in such conditions does not allow for the full expression of genetic potential for cognitive functioning and educational attainment, and there is some evidence for this proposal (Bates et al., 2013; Peñaherrera-Aguirre et al., 2022; Rowe et al., 1999; Woodley of Menie et al., 2018). For instance, Bates et al. found lower heritability estimates for adults who grew up in lower status families and concluded that “high levels of SES amplified the effects of genes involved in adult intelligence” (p. 2114). However, other studies have not found such effects (Figlio et al., 2017; Isungset et al., 2022). It may be that there are more specific experiences in lower SES families that influence cognitive development but are not well captured by broader SES or parental education measures, but this remains to be determined.

In any case, broad improvements in living conditions have contributed to the well-known secular increase in performance on cognitive tests in developed nations, that is, the Flynn effect (Dickens & Flynn, 2001; Flynn, 1984; Sauce & Matzel, 2018), although there is evidence for recent (beginning in many cases in the 1990s) cognitive declines in some developed nations (Flynn & Shayer, 2018; Pietschnig & Voracek, 2015; Shayer et al., 2007), including declines in the same family (Bratsberg & Rogeberg, 2018). The reasons for these gains are debated and likely multifaceted, including more years of schooling and better health (Pietschnig & Voracek, 2015), whereas the more recent losses have been attributed to declines in environmental complexity, such as more television (and now smart phone) watching for children and for adults a shift from more cognitively demanding blue- and white-collar jobs to less demanding service jobs (e.g., Flynn & Shayer, 2018; Shayer et al., 2007). The gains and declines, however, vary by age and cognitive domain and thus gains and losses associated with the Flynn effect are complex and not yet fully understood.

When gains are found they are typically larger for fluid than other abilities, potentially implicating cross-generational improvements in FPN functioning. There is also evidence for increases in overall brain volume during the timeframe with the largest Flynn effects (Woodley of Menie et al., 2016). Parallel secular increases occurred for height, which is a strong biomarker of improvements in living conditions especially during the first few years of life when there are substantive gains in brain network development (Giofrè et al., 2025; Halsey & Geary, 2025; Kuzawa et al., 2014; Tanner, 1992). Gains in height, in turn, are associated with reduced disease burden, longer lifespans (Crimmins & Finch, 2006), and reductions in the rate of cognitive aging (Gerstorf et al., 2020). The implication is that reductions in disease burden and nutritional improvements during the preschool years, and presumably prenatally, might have contributed to the Flynn effect, potentially through the fuller expression of the genetic potential related to brain network development. The flip side is that poor early nutrition and disease burden can compromise the typical development of complex brain networks and associated social and cognitive competencies.

The second broad issue is based on a life history perspective whereby early experiences are predicted to modify brain networks in ways that better adapt them to current conditions. In a review of this literature, McLaughlin et al. (2019) found that the limbic system (e.g., amygdala, medial prefrontal cortex) of children exposed to physical abuse was more reactive to threats and structurally differed from that of children with more benign experiences. These changes potentially reflect an accelerated development of this system and heightened sensitivity to social threats, an adaptive response given these children’s experiences.

A related hypothesis is that scarcity generally and during development increases propensity toward risk taking, short time horizons, and decision making that can compromise long-term success in modern contexts (Mullainathan & Shafir, 2013). On this view, growing up in scarcity contexts could result in an adaptive bias toward achieving short-term goals at a cost of long-term goals and social mobility. This could be why individuals who grew up in lower SES contexts show (on average) hypoactive engagement of FPN and hyperactive engagement of reward networks (Yaple & Yu, 2020). Indeed, experimental manipulations of people’s perceptions of scarcity (e.g., reduced time to complete a task) can result in changes in brain network dynamics, including compromises in FPN and executive functioning in scarcity conditions (Huang et al., 2023; Huijsmans et al., 2019; Jiang et al., 2021). These types of current-demand dynamics are a common feature of the functional plasticity of brain networks (Menon & D’Esposito, 2022) but are not the same as a long-term bias toward preferential engagement of the reward system versus FPN in daily life (Farah, 2017). The unresolved issue is whether long-term exposure to scarcity creates sustained biases in network engagement as a functional adaptation to developmental conditions, or whether adults in lower SES contexts are experiencing downward social mobility because of more inherent biases in network engagement, including the FPN. The latter is likely in some cases (Airaksinen et al., 2021), but in other cases long-term deprivation during childhood does appear to compromise FPN development (McLaughlin et al., 2019).

3. Future Directions

The thesis here is that the study of complex human cognitive abilities and associated conceptual models would be enhanced by following the four questions used to organize the study evolved traits generally (Tinbergen, 1963). The approach was illustrated using the DMN and the FPN, but future studies should take the same approach for other networks that have likely been elaborated during hominin evolution, including the salience network (Menon & D’Esposito, 2022) and the controlled semantic cognition system (Lambon Ralph et al., 2017), as well as more domain-specific networks, such as for language or mechanical reasoning (Geary, 2021). These interact with the DMN and FPN to provide the many unique or enhanced cognitive abilities of humans, including fluid reasoning, abstract conceptual learning, mental time travel, and self-awareness, among others. There are many implications for future studies, and I illustrate a few of them here.

One future avenue is to more fully explore evolutionary and functional relations across the different levels of analysis. For instance, GWAS are very useful, as described by Gargus and Haier (2025), but might be augmented by evolutionarily informed a priori predictions. These would be derived from comparative studies of the genetic correlates of DMN, FPN, and other neural differences across humans and non-human primates, especially chimpanzees (Buckner & DiNicola, 2019; Garin et al., 2022; Posner, 2023). These would also include focusing on genes that influence human DMN and FPN development and functioning and identifying those that differ across humans and chimpanzees. For instance, given the importance of human pyramidal cells for long-range network connectivity, studies might examine species-level genetic differences – or factors that influence gene expression (e.g., microRNA) – associated with the early migration, growth (e.g., dendritic branching), and maintenance of these cells.

The evolutionary model shown in Figure 1 and associated research can also be integrated with studies of ancient DNA and polygenic scores for educational attainment and intelligence. The prediction is that wealth and population expansion will generally weaken the benefits of complex cognitive abilities, such as fluid reasoning, and associated polygenic scores will decline, but the importance of these abilities will increase for populations under stress. This is because the earlier described relation between parental SES and child mortality rates is weakened (or reversed) in stable and growing populations with low child mortality, and thus the competitive advantage (in terms of number of surviving children) of complex abilities declines (Clark, 2007). Kong et al. (2017) found such an effect, that is, declines in polygenic scores for educational attainment, for Icelanders between 1910 and 1990, and Stibel (2021) found similar effects for the United Kingdom and United States (see also Woodley of Menie et al., 2018).

Using ancient DNA, Kuijpers et al. (2022) found that genes associated with educational attainment and fluid reasoning increased as our ancestors transitioned from a hunter-gatherer to agricultural lifestyle and further increased after the transition. The pattern is in keeping with the cycle of larger-scale conflict accelerating with the advent of agriculture and the dynamics shown in Figure 1 (Currie et al., 2020; Hermann et al., 2020; Turchin et al., 2013). Piffer et al. (2023) found a continuing rise in polygenic scores for educational attainment through the emergence and peak of the Roman empire and then a decline after the peak, potentially due to improvements in living conditions and elites having fewer children (Hopkins, 1965); child mortality remained high (Volk & Atkinson, 2013). Thereafter, there was a general increase in polygenic scores for educational attainment as societies grew in size and complexity (Piffer & Kirkegaard, 2024; Woodley of Menie et al., 2017). Identifying the genetic influences on DMN development and functions could be used to test the hypothesis that parietal cortex and parts of the DMN were less developed in Neanderthals than in early modern humans (Balzeau et al., 2012; Bruner, 2018). If confirmed, the implication would be that humans outcompeted Neanderthals in part because of differences in the ability to generate internally focused mental models as part of social strategizing or related abilities (e.g., tool construction).

Although progress has been made (McLaughlin et al., 2019), there are many issues that remain to be addressed regarding the species-typical experiences that promote the development of the DMN, FPN, and other systems (e.g., salience network, language network). These include detailing the minimal necessary social and environmental enrichment experiences needed for the full development of these networks, including the timing and duration of these experiences and whether they differ for different networks. Most of the associated cognitive and brain imaging research has focused on social and psychological (e.g., exposure to abuse, social deprivation) mechanisms (e.g., Gunnar & Bowen, 2021), and these should be expanded to include potential nutritional and other-health related factors (Protzko, 2017). These environmental influences can be expanded to better understand cognitive aging. As noted, the same generations that experienced gains in height and longevity also experienced delays in the onset of cognitive aging (Crimmins & Finch, 2006; Gerstorf et al., 2020). These gains, however, can be compromised by life-style factors, such as obesity, that can contribute to neuroinflammation and compromise mitochondrial energy production that in turn can accelerate cognitive aging (Bhatti et al., 2017; Picard & Turnbull, 2013).

The evolutionary, developmental perspective also leads to the prediction that early experiences might result in adaptive changes in network organization or biased activation of one network or another. There is some evidence for the latter prediction, in keeping with life history theory (Belsky, 2024; Ellis et al., 2023; Tooley et al., 2021), but the nature of the associated experiences and the intensity or duration these experiences are not well understood nor are potential gene by environment interactions. Even with adaptive modification of brain systems, the cost-benefit trade-offs of these adaptations need to be considered. For instance, the heightened sensitivity of the limbic system with exposure to abuse (McLaughlin et al., 2019) might reflect an adaptive response, especially in contexts in which adult relationships are often conflicted. In modern contexts where relationships in adulthood are often more benign (e.g., in work settings), an enhanced limbic system might be a mismatch and create social issues in these contexts.

Although not explicitly addressed above, the evolutionary approach provides unique insights into sex differences in cognition (Geary, 2021, 2025), including sex differences in fluid abilities and variation in these abilities (Geary, 2018; Johnson et al., 2008), as well as in DMN and FPN organization and functions. There is consistent evidence for sex differences in structural, rest-stating and functional connectivity in DMN, FPN and other large-scale networks (Ryali et al., 2024; Shanmugan et al., 2022; Shi et al., 2023; Teeuw et al., 2019), some of which are found in infancy (Fenske et al., 2023). These differences, among others, are related to patterns of gene expression that begin during prenatal development and are influenced by sex hormones, Y-chromosome genes, and X-chromosome genes that escape inactivation (Benoit-Pilven et al., 2025; Oliva et al., 2020; Wapeesittipan & Joshi, 2023). Overall, boys and men tend toward a biased engagement of FPN and girls and women of DMN and show differential engagement of these networks during some cognitive processes (Shi et al., 2023). Future studies might explore how biased engagement of these networks unfolds during complex problem solving and how it influences cognitive biases; for instance, DMN engagement should result in a more self-referential cognitive interpretation of social dynamics.